Belt feed is one of the oldest – and certainly the most popular – high capacity feeding system for small arms. In fact, belt feeding can trace its origins to pre-metallic cartridge, muzzleloading guns era; hose early roots include Edward Maynard's tape priming system and several “chain chamber” guns.

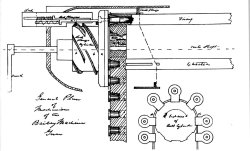

One of the earliest patents for a belt feeding system for metallic cartridge firearms dates back to 1876, when Fortune L. Bailey of Indianapolis (Indiana, U.S.A.) patented a crank-operated rotary barrel weapon with a stationary breech system and forward-moving barrels.

His feed system was unusual in that cartridges remained attached to the belt at all times – before, during and after discharge. This belt consisted of a long strip of cloth with L-shaped metallic tabs attached, featuring tubular cartridge holders. Cartridges were inserted into the holders all the way down to their rims.

The first mass-produced “modern” belt feeding system was introduced by Hiram Maxim for his machine guns. This belt was very simple in concept, consisting of two long strips of cloth or canvas, stitched together to form a series of pockets, equally spaced along the strips.

When loaded, it looked exactly like the contemporary cartridge belts worn by military men and hunters at the time, if longer. Typical personal cartridge belts rarely held more than 50 cartridges, due to the limitations of the human body size; Maxim cloth belts, on the other hand, usually held anything between 100 and 333 cartridges, and sometimes even more.

To ensure accurate cartridge spacing, Maxim added metallic spacers, pinned to the cloth between cartridge pockets. John Moses Browning, who also worked on belt-fed machine guns during the last decade of the 19th Century, used simpler belts with no spacers. Similar designs were adopted by many manufacturers and Armies due to their simplicity and relatively low costs. Cloth belts, however, had certain drawbacks.

The first major drawback of the cloth belt lays in its loop pocket design, which in most cases requires two-stage feed. During the first stage, cartridge is pulled rearwards from the belt and is placed into the path of the bolt. During the second stage, it is pushed forward and into the chamber.

This usually requires some sort of additional mechanism to pull the cartridge rearwards, although Maxim solved this problem by merging several functions (pulling cartridge from the belt, holding it during the feeding process, then extracting the fired case) into the vertically sliding T-slotted breech face of the breechblock.

Other drawbacks included sensitivity of the cloth or canvas to elements, including moisture and cold; and its tendency to stretch with the use or time. Another, less obvious drawback of the cloth belt is an extension of its positive side – the capacity.

The bigger the capacity, the longer the belt... and typical cloth belts holding 250 rounds would measure up to six meters in length when empty. This produces a noticeable “tail” of the partially expelled belt hanging from the gun, which could interfere with movements. As a result, machine gun crews often carried knives to cut the expended empty belts before any combat maneuver.

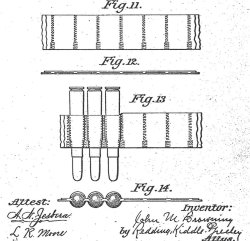

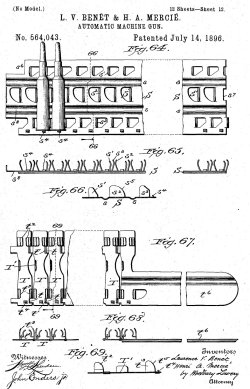

Complications, associated with two-stage feed of the cloth belts were first solved by Lawrence Benét and Henri Mercié at the French-based Hotchkiss & Cie. company. Their patent from 1896 described several types of metallic belts with simple, open-top cartridge pockets formed by “fingers”, stamped and bent out of the sheet steel or brass base.

The patent described rigid belts or “strips”, typically associated with famous line of Hotchkiss machine guns of WW1 fame, but also included semi-rigid and fully rigid belts, assembled from three- and single-cartridge units, connected by hinges. Rigid strips were produced by Hotchkiss for their machine guns in various capacities, ranging from 9 to 30 rounds. Semi-rigid designs were usually encountered in 50-round capacities (for use in early tanks) and in 250-round capacities for use in anti-aircraft installations (during WW1). Produced from steel or brass, these rigid and semi-rigid belts found wide acceptance in variety of Hotchkiss machine guns (medium guns such as the M1914 and lighter models such as the M1909 “Hotchkiss Portative” or the M1922).

Similar feeding systems were used in the Japanese Type 03 Taisho and Type 92 medium machine guns, which were heavily influenced by the Hotchkiss design. As a result of the open-pocket design and fixed spacing between cartridges, Hotchkiss machine guns featured a simple and rugged feed system which easily positioned strips with fresh round in front of the open bolt. Forward movement of the bolt then pushed cartridge forward and into the barrel.

Of cause, this system has its own drawbacks. Strips were relatively heavy and offered limited capacity; the 30-round strip was almost 40 cm long and could be easily bent or otherwise damaged by rough handling during the combat.

Limited capacity also required more attention from the loader, to keep the gun firing for long periods. Shorter strips were issued for M1909 “Hotchkiss Portative” light machine gun, but these limited sustained fire capabilities even further. Empty feed strips also required additional care before reloading, to ensure that tabs holding the cartridges wouldn't bend or break causing malfunctions and failures to feed. Normally, machine gun crews were issued with special tools to maintain reusable feed strips.

It must be noted that this basic system was further developed in France and Italy, albeit with questionable results.

First, the French government Puteaux arsenal (APX) designed its own version of the rigid feed strip for its abortive Puteaux M.1905 machine gun (later evolved into the equally unspectacular St.Etienne M1907 machine gun).

To circumvent Hotchkiss patents, APX designers built their strips with closed loops at the front, which required a two-stage feed.

This, in theory, would also enhance the reliability of cartridge positioning. The only positive result of this design was that the resulting gun could be easily modified to use longer cloth belts.

Italians used similar arrangement in their Breda Model 1937 medium machine gun. Instead of small tabs, stamped and bent out of the strip base, Breda feed strips used large T-shaped partitions that held cartridges along their entire length.

This resulted in more positive and reliable feed, but also noticeably increased cost and weight of the strips. Another drawback of this machine gun was that it was designed to place empty cases back into the strip, requiring crews to clear them first from before reloading with fresh ammunition. Italian strips also offered very limited capacity of 20 rounds each, way too insufficient for a tripod-mounted medium machine gun.

The evolution of military aircrafts brought up several new problems. One was that expended parts of the cloth belts tended to escape into airflow and strike pilots in the face or jam various exposed controls. As a result, several types of disintegrating steel belts were produced for aircraft machine guns. These belts consisted of separate links, each connecting two adjacent cartridges.

Links were connected into the belts of any size by using cartridges as removable connectors. Early disintegrating belts were designed for machine guns that originally were designed for cloth belts, and thus featured two-stage feed systems.

Therefore, typical links had “8”-shaped design, when viewed from the front or from the rear. Once the cartridge was pulled out of the link and fed to the gun, empty links were expelled from the gun and either discarded into the air (preferably below the airplane) or collected into special container for later disposal or reuse.

An interesting belt design appeared during the WW2 for tank use. British tanks of the era used Czechoslovak-designed BESA machine guns chambered for the 7.9x57mm cartridge.

These guns were originally built for open-pocket non-disintegrating steel belts.

However, these belts were not flexible enough for use inside the cramped compartments of the tanks, and British designers produced a combination cloth-steel belts which combined flexibility of the cloth with open pockets, formed by C-shaped steel clamps attached to the cloth.

After World War 2, most armies gradually replaced cloth belts with steel belts. New NATO-standard machine guns would usually feed through open-pocket disintegrating belts manufactured out of spring steel and featuring “3-shaped” links.

The most notable designs featuring this kind of feeding system include 7,62x51mm NATO general-purpose machine guns such as the Belgian FN MAG or the American M60 as well as light machine guns and section automatic weapons in 5,56x45mm NATO such as the FN “Minimi”, the Heckler & Koch MG4 and the newer 7,62mm-caliber MG5. Some older designs may however still be found in operational conditions and using non-disintegrating, open pocket belts – that being the case of the 7,62x51mm caliber MG42/59 or MG3, both direct descendants of the WW2-era MG42

Some others, such as the Browning designs (.30-caliber and 7,62x51mm caliber M-1919 and M37 models, or the ubiquitous 12,7x99mm M2HB), will feed from disintegrating closed-pocket links.

The Russian forces, on the other hand, kept using non-disintegrating, closed-pocket steel belts for their 7.62x54R Kalashnikov PKM general-purpose machine guns. These belts are noteworthy for being still compatible with older Maxim M1910 medium machine guns.

Russian weapons designed for rimless ammunition, such as 7.62x39 Degtyarov RPD or 12.7x108 NSV and Kord heavy machine guns, use non-disintegrating, one-stage feed steel belts with open pockets, normally assembled from 10-, 25- or 50-round pieces to avoid long tails of empty belts dragged behind the gun on the move.

Plastic belts are noteworthy for the final part of our treatise: polymer belt links have been in development for several decades now, but are still quite far from general adoption, despite the obvious advantages in terms of lower costs and weight offered by modern composite materials.

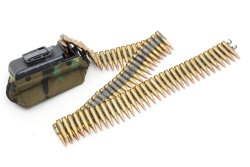

Speaking of ammo belts in general, readers should also take note of the fact that in real life, ammo belts are seldom – if ever – carried wrapped around the body or the forearm of the shooter, or just left hanging around the machine gun, “Rambo-style”.

Belted ammunition is sold from factory or issued from ammo depots in cases or boxes, each containing one complete and loaded belt; said containers can be laid on the ground next to the gun or attached to its mount when firing from a fixed position.

Reusable belt containers, attached directly to the gun – generally in front of the trigger guard and under the feed tray – are also an alternative, offering superior mobility.

The earliest examples of this type of containers were usually round in shape, while modern containers are often rectangular in shape, and of lighter semi-rigid design while older designs were limited to rigid stamped steel structures.

For special purposes – particularly for assault units – some Countries developed backpack-type belt boxes offering anywhere between 200 and 500 rounds in capacity out of a single belt, usually connected to the machine gun through a rigid metallic chute.

In most cases, such designs have been or still are employed only on a “semi-official” basis by various Special Forces. As a matter of fact, an early backpack belt-feed system for the M60 general-purpose machine gun was field-tested by U.S. forces during the Vietnam War

In conclusion, we must briefly mention belt-loading machines – quite useful for armorers who have empty belts to fill and boxes of loose ammunition. Hand-loading of ammo belts is a long and tedious work, so belt-loading machines were designed in many Countries as the technology of belt-feeding machine guns evolved.

As of today, the armies of most western Countries employ factory-loaded, disintegrating link ammo belts that are discarded after use. Many military forces, however, still use reusable non-disintegrating belts – and that's where belt-loading machines turn in handy.

A good example of such a useful implement is the Rakov-designed belt-filling machine of Russian origin: it's a crank-operated device, featuring a hopper for loose cartridges and a belt drive. The operator just drops a number of loose rounds into the hopper, inserts the empty belt and turns the crank; what he gets is a loaded belt with little effort.

Read more

"Feeding the beast": high-capacity magazines for automatic weapons