Since the telescope was invented, there had been attempts of making a version which could be used with both eyes. The first “binoculars” were reported as early as 1608. Until 1854, when Ignazio Porro patented a system to erect the image observed thru the instrument through the use of prisms, binoculars were essentially of a Galilean type. In fact, only towards the end of the 19th century the first true prismatic binoculars would see the light of day. They were the product of a joint effort led by optics designer Ernst Abbe, who would refine Porro’s set of prisms, Otto Schott, a manufacturer of glass-made optical material and Karl Zeiss, a manufacturer of optics instruments. Together they would develop an impressive amount of instruments, including the first modern binoculars using Porro-style prisms – an 8x20 magnification instrument – in 1894.

Modern binoculars are a high-precision optical instrument, with the aim of providing three-dimensional images of the object observed by the viewer. They are made out of two telescopes which are paired together in order to allow for the use of both eyes at the same time.

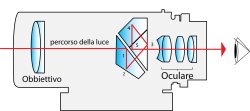

A telescope is composed of a lens which captures the light and sends it to an eyepiece. This magnifies the image and sends it back to the eye of the observer.

Thus, binoculars appear to be quite a simple object, but in fact their manufacturing is rather complex in technical terms – i.e. the trouble lies in the correct alignment between the two optical instruments and in achieving their optical coherence, as they need to be exactly identical.

The simplest version of a telescope sends back an image which has been rotated by 180 degrees, so that in practice we would see it upside down.

Unlike most telescopes, which rely on a set of additional lenses to straighten the image, modern binoculars employ a set of prisms both to rotate the image and to reduce the instrument size (by folding the path taken by the light beam). Nowadays two optical schemes are usually employed. One includes a pair of prisms arranged according to the traditional Porro configuration, while the other is based upon a two-roof prisms scheme.

It is easy to distinguish one optical scheme from the other. All binoculars where lenses are staggered with respect to eyepiece axis are equipped with a Porro prism, while coaxial eyepiece binoculars have roof prisms.

Manufacturing binoculars with roof prisms is more expensive and more difficult than traditional ones employing Porro prisms. In addition, due to a greater number of air / glass light path passages – at least in the Schmidt-Pechan configuration, which is the most widely used because of its consistency – a greater internal dispersion of light can occur. Schmidt-Pechan roof prisms also require special surface treatment for phase correction (shortened in PC). This is usually done in order to avoid loss of contrast and/or additional chromatic aberrations (such as interference), as well as to create brand-new refraction surfaces (mirrors) , which respond to excessively small refraction angles which are not sufficient in attaining the total internal refraction which is given when exceeding the critical angle. The Abbe-Koenig prism also exists which is, however, much more cumbersome in binocular design.

Furthermore, although the use of roof-prisms usually makes for more compact binoculars, the greater distance between the lenses-axis as ensured under the traditional Porro prism scheme allows for a deeper three-dimensional perception of the objects observed, even at considerable distance. If we compare two binoculars with similar performance and specifications, all other things being equal – i.e. quality of materials used and quality of the manufacturing process – the one equipped with roof prisms will have a considerable advantage in terms of ergonomics, short-distance focus possibilities (less than 3 m) and an excellent eye relief value (from 16 mm up), in addition to having a lighter weight, a smaller size and a cleaner and more elegant look. However, the binocular equipped with traditional Porro-style prisms will score better in terms of optical performance, while providing a deeper three-dimensional view with cheaper costs of production. From a quality point of view the gap between the two has recently narrowed. As a result, high-end roof prisms binoculars are practically able to match the performance of traditional binoculars. Unfortunately, quality does come with a price. Quality being equal, binoculars with roof prisms are usually 25 percent more expensive than traditional ones.

The current trends, which are heavily driven by consumers’ esthetic taste, have recently set in favor of those products equipped with roof prisms. As a result, big manufacturers have oriented their research and development efforts in this direction.