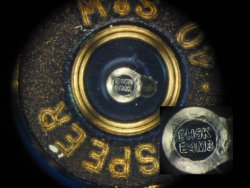

Like bad news, bad ideas always spread fast and far. And the State of California is an interesting case study when it comes to bad ideas about firearms legislation. One of the most curious examples is “microstamping”. This is a technology by which microscopic markings, engraved onto the tip of the firing pin with a laser, are transferred to the primer by the firing pin and to the cartridge case when the gun is fired.

The microscopic markings imprinted on the ejected cartridges can then be examined to trace the firearm to the last registered owner.

California requires that all semiautomatic handguns sold in the state not already on the California approved handgun roster incorporate microstamping technology and no new gun can be certified for sale unless it incorporates a “microstamping” process.

This law, passed in 2007, generated controversy and at present is still on hold, with the ongoing litigation in the hands of the California Supreme Court.

The bad news, after the bad idea, is that Democrats have recently introduced a new bill to the US House of Representative that would make the microstamping mandatory and would strip the ability of all federal firearms licensees to sell pistols that do not carry the microstamping technology.The bill's author, U.S. Rep. Anthony Brown, D-Md., stated that “Microstamping offers law enforcement the chance to track bullet casings to the source of the crime, and is one more step we can take to ensure the safety of the American people.”

An “unreliable and easy to defeat” technology

So, what's wrong with microstamping? First of all, the technology itself: many argue the current state of the technology does not allow for imprinting on the hard surface of the cartridge casehead or to imprint consistently and legible identification information on a casing primer from the tip of a firing pin. The National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) claims that “it is not ready for use as a crime solving tool” and that it's “unreliable, easily defeated and simply impossible to implement.” Incidentally, it must also be noted that microstamping is a proprietary patented technology presently owned by a company called NanoMark, the only company from which this technology can be purchased.

Besides that, firing a large number of rounds will wear down the microstamp even after a few shots, quickly making it illegible: “Placing a microscopic mark on a firing pin is like placing a car's vehicle identification number on the tire tread. It just doesn't stand up,” to use NSSF words.

Just use a bat. Or a revolver.

On their part, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute (SAAMI) pointed out that criminals could simply collect microstamped cases from a firing range and leave them at the scenes of their crimes, thereby providing false evidence against innocent people and messing up or misleading the investigation.

Moreover, microstamping can't be applied to revolvers, since they don't eject empty cases. Lastly, criminals often use stolen guns, so finding the original owner is perfectly useless.

On the web, you can already find a series of simple options for criminals to defeat microstamping. Some are jokes, others are not.

Here are a few:

- File off the firing pin markings (the depth of the laser engraving is approximately 0.005 inch, which is vastly smaller than the tolerance of the firing pins drive depth.)

- Use an alternate firing pin (they are cheap and readily available.)

- Use one of the millions of non-microstamping pistols already in circulation.

- Put small patches of duct tape on cartridge primers before shooting.

- Use a home-made brass catcher to collect spent cases.

- Use a revolver.

- Use a bat. (Yes, this is the joke. Almost.)

What is clear is that microstamping isn't cheap: the NSSF estimates the cost will be upwards of 150 US dollars per firearm.

All in all, it seems that the only goal that can be achieved with microstamping is making more costly for law-abiding citizens to get a gun. Outlaws won't even pay attention to it.