Recoil is one of earliest and most successful working principles for autoloading firearms, and was found to be adequate for a surprisingly broad spectrum of weapon systems, from pocket-sized pistols up to heavy machine guns and automatic cannons. There's however a noticeable gap in the spectrum of recoil-operated firearms; to be specific, very few successful hand-held long guns (especially rifles) ever used recoil operations, and we shall see why.

Recoil is a basic property of every firearm, and it is a direct consequence of the Newton’s 3rd law of motion – the one that postulates that every action causes an equal and opposite reaction. This means that the expulsion of a bullet from the barrel of a gun by the pressure of hot powder gases causes the barrel itself – and thus the gun as a whole – to receive an equal impulse to that of the aggregate impulses of the projectile and gases, but in an opposite direction. In turn, this transmits a rearward movement impulse to the gun – an impulse that is felt by the shooter as recoil. In fixed barrel, locked breech firearms – basically, in all manually-operated guns – recoil is directly transferred in its entirety on the shooter's hands and shoulders, or on a supporting mount if one is in use.

Hiram Maxim, an American inventor living in Europe, was probably the first person to successfully exploit the otherwise wasted recoil energy to automatically cycle the action of a firearm.

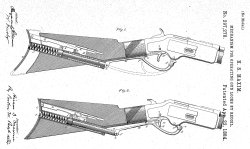

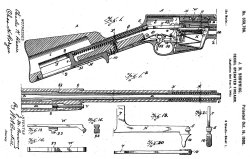

In his first firearm-related patent – which he filed in 1883 and received in 1884 – Maxim described a conversion of a manually operated Winchester lever-action rifle that used recoil to cycle the bolt and chamber a new round from a built-in magazine tube. Maxim achieved said result through a spring-loaded buttpad, attached to the shoulder stock: recoil transmits a rearward movement to the entire gun, while the buttpad remains stationary against the shooter’s shoulder, ideally putting a series of levels into motion, which would cycle the gun.

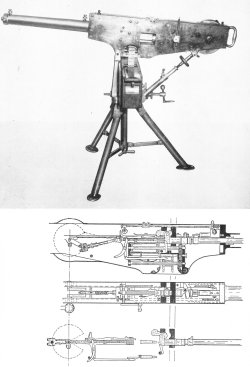

This design, purely experimental in nature, eventually led to the development of the world's first practical and successful automatically-operating machinegun of all times – the Maxim gun. In the Maxim gun, the barrel and its extension, along with the breechblock, are allowed to recoil inside a stationary receiver and compressing a return spring; this rearwards movement cycles the the breechblock, the spent case is extracted and ejected, while at the same time the belt-feeding unit operates to load a fresh round in chamber.

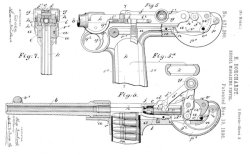

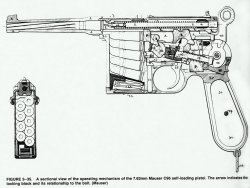

This basic principle found a wide acceptance very soon among gun technicians and designers in many Countries all around the world: Hugo Borchardt applied to patent a recoil-operated pistol design in 1893; Fidel, Friedrich and Josef Feederle – three technicians working at Mauser – developed their recoil-operated pistol which would be come famous as the Mauser C.96 in 1894; and John Browning patented his first recoil-operated pistols in 1896.

By the turn of the 20th century, recoil operation was firmly established as a practical and successful technical solution for autoloading firearms. It must be pointed out that gas-operated action had been widely known for at least one decade before the turn of the 20th Century; it however found very little acceptance for quite a while, remaining vastly outshadowed by various recoil-based working systems.

The key reason behind the initial superior popularity of the recoil operation over gas operation is that recoil operation depends purely on the impulse of the propelled projectile, allowing technicians to disregard the complex (and not yet properly explored and researched, back then) dynamics of the gas pressure build-up and of their subsequent drop back to ambient pressure.

Plus, by the late 19th Century, smokeless powders were relatively new and marked by a great market variety and a likewise vastly discontinuous performance, while shotgun and even rifle ammunition was still occasionally loaded with black powder; this was typically cause of additional complications for gas operated actions. On the other hand, recoil-operated actions were – and still are – much more forgiving to variations in power loads and other changes in internal ballistics, as long as the overall recoil impulse of the round would stay within certain limits.

The main drawback of the recoil-operated actions against gas-driven systems is that the former always requires a sliding or recoiling barrel; in order to achieve an acceptable degree of reliability – especially when facing unforeseeable varying conditions typical to military and even hunting uses – the recoiling barrel must have some degree of mechanical play, or tolerance, within the gun to avoid being easily jammed by the thermal expansion of the steel, by fouling or by other external elements such as dust or sand. This necessary degree of play, obviously, causes a decrease in accuracy – a generally undesirable factor in all firearms, and particularly in long-range rifles. Another downside of recoil operation lays in the fact that a moving barrel must be supported and guided in its rearwards travel not only at its rearmost portion, but also at the middle and at the front.

And this requires the use of a barrel jacket – a common feature among most recoil-operated firearms, from the earliest Maxim machine-guns and Browning rifles to many successful designs of the following years, such as the German Mg.34 and Mg.42 machine-guns.

However, some more or less successful recoil-operated firearms indeed do without a full-length barrel jacket: that's the case of the Browning Auto-5 shotgun (whose barrel is supported around the middle portion by a ring that slides along the feeding tube), the Browning M2-HB heavy machine-gun, and the Johnson Model 1941 military rifle (whose relatively short barrel jacket supported the rearmost third of it). Obviously, a barrel jacket adds to the weight and the cost of the gun – in both cases, an undesirable side effect.

As a result, the number of recoil-operated rifles of any type to reach mass production is relatively small; the aforementioned Johnson M1941 is probably the most successful military recoil-operated rifle, manufactured in several tens of thousands in the early phases of World War II. The most successful recoil-operated rifles ever made are John Browning's Remington Model 8 hunting rifle and its most direct derivative, the Model 81: overall, Remington manufactured about 140.000 of those rifles between 1906 and 1950.

On the other hand, recoil-operated pistols were – and still are – manufactured by the millions each year worldwide; recoil-operated machine guns, while less popular today than 50 or 100 years ago, are still kicking and ticking in many parts of the world, although mostly in older, time- and war-proven designs such as the Browning M2-HB or the MG3. The evolution of propellants and of the knowledge of internal ballistics gradually made gas-operated machine-guns more cost-effective than recoil-operated designs – but this will be topic for our next article.

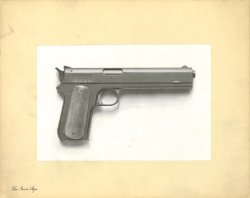

As of today, semi-automatic pistols are still the most widely used type of recoil-operated firearms. Virtually all pistols designed in the past 120 years to use military-type ammunition are based on some form of short recoil operation; in the vast majority of cases, they're based on the Century-plus old design patented by firearms genius John Moses Browning, who also designed many other successful recoil-operated firearms such as the first ever successful semi-automatic shotgun – the Browning Auto-5, or Remington Model 11 – as well as one of the first mass-produced sporting semi-automatic rifles (Remington Model 8) and a number of machine-guns. Ironically, exception made for his handguns, the only other Browning designed recoil-operated firearm still in widespread use is the Browning M2-HB heavy machine-gun.

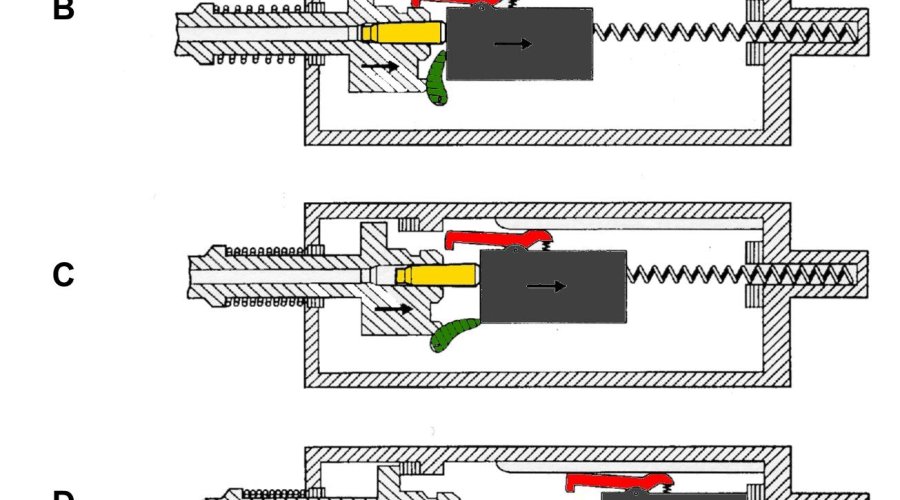

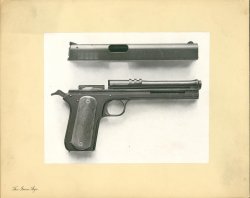

Two distinct types of recoil-operated working systems for firearms exist: the “Short recoil” and the “Long recoil”. In this context, “short” and “long” refer to the relative length of the recoil path that barrel and breech block follow together before unlocking.

In short recoil operation, the breechblock travels very shortly – about 0.5 to 3 millimeters, depending on the cartridge length – before unlocking; once it does, the barrel stops its rearward movement while the breechblock continues its cycle alone, extracting and ejecting a spent case and feeding a fresh round in chamber.

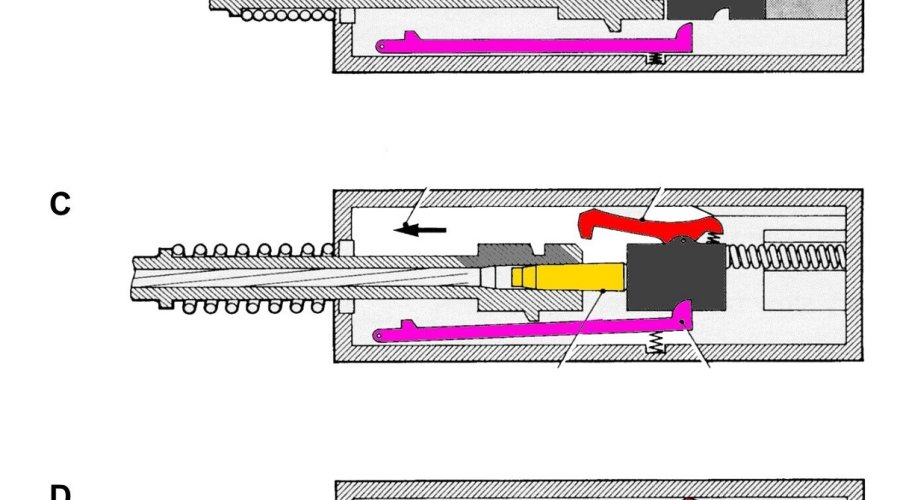

In long-recoil systems, the barrel and breechblock recoil and stay locked together for the entire length of the cycle; once the breechblock reaches the end of its rearwards travel, a special sear captures it and holds it in position while the barrel starts to move forward under the pressure of its own return spring. The initial forward movement of the barrel unlocks it from the breechblock, which retains the spent case through the extractor claw while the barrel keeps on sliding forward.

Once the empty case is left clear of the chamber, it can be ejected; and when the barrel reaches the end of its return travel, it automatically engages the bolt release lever, allowing the breechblock to shut close under the pressure of its own spring, loading a fresh round in the process and readying the gun for the next discharge.

In most long guns – rifles and carbines, shotguns, machine-guns, etc. – the barrel is noticeably heavier than a breech block; therefore, after unlocking most of the overall impulse “remains” with the barrel.

If left untamed, this energy is basically wasted and remains with no practical use; however, many short recoil operated long guns feature so called “bolt accelerators”, which, once bolt is unlocked from the barrel, transfer some of the barrel impulse to the bolt, further accelerating the latter while slowing down the former before the barrel is completely stopped.

In handguns, where the barrel's weight is usually comparable to that of the breechblock, there is very little use of accelerators; the only noteworthy pistol to have ever been produced with an accelerator was the Finnish Lahti L-35, a firearm with a relatively short slide that was intended to be used in the unforgiving conditions of Nordic winters.

As we have seen, recoil operated systems have many merits, most important of them all being the relative insensitivity to the propellant performances as long as the cartridge generates an adequate level of recoil. The key disadvantage of all recoil-operating systems lies in the sliding barrel design, which requires additional support and decreases long-range accuracy.

See also: