In our previous article, we discussed the simplest form of automatic working systems for firearms, known as “blowback”, or unlocked breech action. In this article we will discuss a slightly more complicated form of unlocked breech principle, known as “delayed blowback” – also referred to as the “retarded” blowback by some sources. Essentially, this system works the same way as the straight blowback – it relies on the pressure exerted by the powder gases onto the base of the cartridge case, pushing it backwards to counter the inertia of the breechblock and the strength of the return spring. However, in this particular case, some mechanical or physical means are implemented to slow down (retard, delay) the initial opening of the breech block while bullet is still traveling through the bore and thus the pressure inside the bore, case and chamber is still high. There are many forms and implementations of delayed or retarded blowback systems, mostly developed before World War II or shortly afterwards. Not many were successful – and we'll try to see why.

The difference between “delayed” and “retarded” blowback lays basically in the fact that in “delayed” blowback systems, the breechblock is momentarily stopped after first several millimeters of rearward travel, to ensure that thin cartridge walls are still supported by the chamber while pressure is still high, and only a small part of a relatively thick cartridge base is exposed; once the bullet is out of the bore and pressure is down, bolt is left free to cycle under remaining pressure and/or inertia of the bolt carrier.

In “retarded” blowback systems, the breechblock moves continuously from the very start, but its initial opening movement is slowed down by technical features.

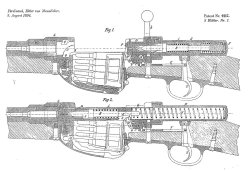

The first delayed, or retarded, blowback actions were patented in Europe shortly before the turn of the 20th Century. Some of those most notable – although unsuccessful – early systems were patented by famous Austrian gun designer Ferdinand von Mannlicher.

One of his earliest self-loading designs was patented in 1893, and regarded a military rifle with a “self-unlocking” rotary bolt sporting angled bolt lugs that entered spiral cuts inside the receiver.

The general idea was that the friction between the bolt lugs and their mortises in the receiver would slow down the initial phase of the bolt opening, allowing it to self-unlock under the pressure.

However, the system turned out to work too violently, resulting in many split cases. Later on, a similar system was used in the U.S.-designed Thompson automatic rifle and in the Italian FIAT Model 1914 “Villar Perosa” machine-gun; of the two, only the latter offered a more or less reliable operation, given to the fact that it was chambered for relatively low-powered and short handgun ammunition.

In fact, it would have probably worked equally well with a straight blowback system, if a bolt heavy enough was implemented.

The most successful early delayed/retarded blowback weapon was probably the Steyr Mod.1907/12 machine-gun, designed by German engineer Andreas Schwarzlose around 1905 and adopted by the Armies of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, Sweden, and other European Countries. Widely used during World War I, the Schwarzlose Mod.1907/12 machine-gun remained in service well into World War II in Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the Netherlands.

To ensure reliable extraction with its prematurely opening breech, the Schwarzlose machine-gun featured a built-in oiler that applies a small amount of lubricating oil to each cartridge during the chambering process. This helped to avoid cases sticking in the dirty or overheated chamber, which otherwise would result in stoppages or catastrophic gun failures due to torn case rims or separated cartridge heads.

A knee-shaped arrangement of two levers supporting the block – in a manner similar to a toggle lock – would retard the opening of the breechblock. A similar solution was later used in the 1920s by American engineer John Pedersen for his prototype self-loading rifles. Pedersen's toggle-lock setup was slightly different from Schwarzlose's system, although the use of lubricated ammunition was a common feature – in Pedersen's case, each cartridge would be factory-lubricated with a wax-like coating. Pedersen rifles operated well, but not well enough, especially when it was decided to switch them from their native, relatively mild .276 cartridge (7x51mm) to the noticeably more powerful .30-06 (7.62x63mm) caliber. As a result, the Pedersen rifle layout eventually lost it to John Garand's gas-operated rifle design.

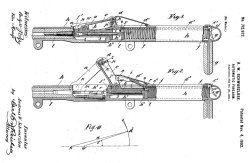

The next firearms to enter mass production and use a delayed blowback system – in which the rearward travel of the breechblock would actually stop during the reloading cycle – were the MKMO and MKPO sub-machine guns, designed in Switzerland by Pal Király and Gotthard Ende and manufactured by SIG from 1934 until 1937. Those SMGs were typical Swiss designs – extremely finely crafted, mechanically complicated and rather expensive. Not surprisingly, only a handful of those were made and sold – most notably to Vatican guards – before SIG engineers re-engineered them into a simple straight blowback designs known as the MKMS and MKPS.

In the original MKMO/MKPO setup, the relatively small breechblock (bolt) had a projection at its rear top which engaged the rear edge of the top ejection port in the receiver, stopping the bolt after initial 6 mm of rearwards travel. The massive bolt carrier starts its recoiling movement along with the breechblock and continues its rearward cycle while the breech block is stopped (delayed) by its projection. After some free movement, the bolt carrier engages the ramp surface at the bottom of the bolt and tips its rear end down, disengaging it from the receiver. Once the bolt is fully tipped down, the bolt group continues its rearward movement by sheer inertia and residual bore pressure. This may sound unnecessarily complicated for most pistol-type cartridges – and indeed it was, given how the design was later converted to straight blowback.

While SIG in Switzerland switched to standard blowback for its subsequent line of sub-machine guns, Pal Király moved to Hungary to continue his developments in the field of delayed-blowback sub-machine guns.

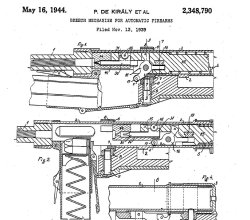

Here he eventually gave light to one of more popular implementations of delayed/retarded blowback system, using a two-part bolt with a retarding lever. In this system – originally patented as early as in 1910 but practically implemented in a production-grade firearm only in 1939, in the Danuvia 39M sub-machine gun for the Hungarian Army – a relatively light bolt is complemented by a heavier bolt carrier.

A simple two-armed lever is attached to the bolt head through its pivot axis. When bolt is closed, the lower arm of the lever rests against the stationary “shelf” in the receiver, and the upper arm bears against the front of the bolt carrier. Upon discharge, the rearward movement of the bolt head causes the lever to rotate and push back the bolt carrier with greater velocity, thus momentarily increasing its inertia force exerted against the pressure of powder gases.

Once the initial “retarded” movement of the bolt head is complete, the lower arm of the lever leaves its seat in the receiver; from this moment on all parts of the bolt group recoil as one, under the residual gas pressure and moving parts inertia. Such a system worked more or less well with handgun cartridges, but was in fact redundant due to inherent low pressures in sub-machine guns and their ammunition. This same system was later more or less successfully developed by French engineers and implemented first in their 7.5x55mm AAT M52 general-purposes machine gun, then in the 5.56x45mm FA-MAS assault rifle. In either case, this system worked “reasonably well”, but it proven to be too sensitive to headspace issues and to the quality and materials used in cartridge cases (that's particularly the case of the FA-MAS).

As a historical curio, we can point out that between the 1950s and the 1960s, Soviet designers developed a number of experimental assault rifles and light machine guns based on a Király-type lever-retarded system. Those systems proved to be noticeably simpler and cheaper than the Kalashnikov-type gas-operated system, and also offered tighter patterns in full-automatic fire. However, all these system were found to be inherently less reliable than Kalashnikov's, particularly under harsh environmental conditions. As such, all were dropped out of competition.

Despite a somewhat marginal level of popularity and success of the delayed and retarded action systems during the first half of the 20th Century, one specific German company went on to become its strongest proponent from the 1950s onward – and as a matter of fact, said company reached global success particularly due to its line of delayed blowback-operated firearms. That's right: we're talking about Heckler & Koch and their roller-delayed blowback system.

The origins of this system can be traced to two contemporary German developments dated back to 1944-45 era: the experimental Grossfuss Mg.42(V)/Mg.45 general-purposes machine gun and the Mauser Gerat 06(H), also known as the StG.45(M). Both systems were based on the roller-locked action first seen on the highly successful Mg.42 machine gun.

In both cases it was found that by careful redesign, a rigid locking system could be replaced with a self-opening system in which rollers act as retarding means for the bolt head, at the same time accelerating the heavier bolt body while riding inclined surfaces in the barrel extension.

This system was refined in the 1950s by Ludwig Vorgrimmler and other German engineers who emigrated to Spain after the end of World War II; there, it was first successfully implemented in the CETME Model B battle rifle – later licensed for manufacturing to Heckler & Koch in Germany and thus adopted by the German Army in a refined form as the G3 rifle, in 1959.

Inherent extraction issues typical to delayed/retarded blowback systems were solved by the use of so-called fluted chamber that allows some powder gases to flow rearwards from the bore through the flutes, thus providing some pressure compensation from outside of the cartridge case, decreasing the friction during the initial, high pressure stages of blowback.

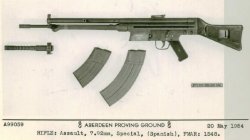

HK engineers developed a broad family of small arms based on the roller-delayed blowback system, which included the G3 as the parent weapon as well as the 7.62x51mm caliber HK-11 light machine-gun and the HK-21 general purposes machine-gun; the 9x19mm and .45 ACP caliber P9S pistol; and one of the most successful sub-machine guns in history, the MP5 line of 9mm, .40 Smith & Wesson and 10mm Auto SMGs.

The second generation of HK's roller-delayed weapons system included 5.56x45mm NATO entries such as the HK-33 and G41 rifles, the HK-13 and HK-23 light machine-guns, and the 7.62x51mm PSG-1 and MSG-90 sniper rifles. The G3 rifle met significant international success, being adopted by at least 30 militaries worldwide and produced under license in several Countries including Turkey, Pakistan and Iran.

The MP5 is still an international hit, adopted by God knows how many militaries and law enforcement organizations around the world.

Today, the Heckler & Koch MP5 remains the only mass-produced delayed/retarded blowback firearms, despite the fact that similar results in terms of accuracy and controllability with 9x19mm caliber ammunition can be easily obtained with simpler and cheaper straight blowback designs.

A similar roller-delayed system was also used in a small number of other weapons, such as U.S.-manufactured CALICO line of firearms and the most recent SRM-1216 semi-automatic shotguns. And still, no other weapon with similar action could compete with MP5 in terms of popularity and success

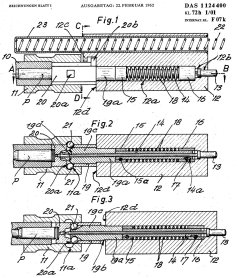

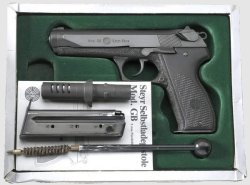

Another German-designed type of retarded blowback action, using gas pressure to slow down the initial opening of the breechblock, was far less successful: first developed in 1945 by Rheinmetall engineer Karl Barnitzke for the VG.1-5 Volkssturm semi-automatic carbine, it was later implemented in modified forms on pistols such as Austrian-made Steyr-Mannlicher GB, and the German Heckler & Koch P7. In the case of the VG.1-5 rifle and the Steyr GB pistol, powder gases were fed from the bore through dual ports into a sliding cylinder fitted around the barrel; there, they expanded and exerted pressure against the rear-shaped fore-end of said cylinder, which in turn was connected to the breechblock. In the Heckler & Koch P7 pistol – and in the derivative pistol designs of later years, including the Walther CCP and South African handguns such as the ADP and the Vektor CP1 – the gas cylinder was located just under the barrel. In all cases, the gas-retarded system was found to be prone to rapid overheating and fouling.

Overall, we must conclude that delayed/retarded blowback systems never became too popular: its advantages were marginal over straight blowback when it came to the management of low-powered pistol-caliber ammunition, and furthermore its implementation is guaranteed to be much more expensive.

When it comes to more powerful firearms chambered for intermediate or full power rifle calibers, the relative simplicity of the unlocked breech system is offset by a sharp decrease in reliability and a inherent high sensitivity to extraction issues and cartridge case materials.

One good example of the latter issue can be found in the performance of modern composite (polymer/metal) case ammunition, which works reasonably well in locked breech designs but causes dismay results in delayed blowback actions with fluted chambers.

See also: