Typically, firearms can be separated into the two large categories – manually-operated or selfloading.

Manual repeaters require the shooter to deliberately work on mechanisms that will extract the spent case, load a fresh cartridge and re-cock the firing mechanism before the next shot can be fired. Selfloaders will do the same all by themselves, without any direct intervention from the operator.

Said selfloading firearms can be further split into several classifications and categories – the first of which is based on the source of energy to cycle the action to distinguish between a very large subclass of autoloaders that use the energies generated by a previous shot to prepare for the next, and a relatively small subclass of systems whose action is cycled through an externally-powered system such as an electrically-driven or hydraulic motor.

In the coming series of articles, we will discuss a plethora of operating systems for firearms, starting with the simplest form of them all – the blowback action, using gas pressure to cycle the action.

First of all, it should be pointed out that the vast majority of modern firearm cartridges – exception made for some very specific “captive piston”-style, integrally-silenced design – are too weak to contain the pressure generated by the burning propellant. The cartridge has thus to be supported at its sides by the walls of the chamber, and at the rear by the breechblock face.

The pressures generated by a centerfire cartridge being fired are typically in the ranges of 2 tons per square centimeters and up, although this force is exerted only for a very short amount of time. Most early manually-operated firearms featured some form of rigid connection between the breechblock and the barrel at the moment of firing; making those systems automatic was not an easy task, but simple inertia physics came to help here.

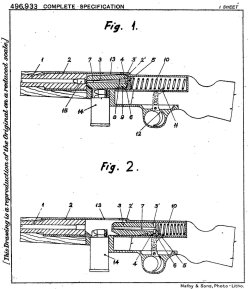

It was found that the use of an unlocked, horizontally-sliding breechblock supported from behind by a spring would be enough to hold the cartridge inside the chamber while the bullet traveled down the bore and the pressure within the system remained high.

Of course, in this case the cartridge and the breechblock would be moving rearwards right from the very moment of the ignition, but in a properly designed blowback system said movement would be too short to expose the cartridge walls until the pressure has dropped considerably.

Another benefit of this system is that this initial movement and residual pressure gives the empty case enough momentum to be ejected from the barrel and out of the gun as soon as the gun unlocks, thus automating the first part of the cycle.

The heavy breechblock, acting on its own inertia, compresses the spring up to the maximum level; once the breechblock reaches the rearmost end of its travel, the spring is decompressed to slam it shut again, loading a fresh round and closing the reloading cycle.

Depending on the system, the separate hammer or striker will also be reloaded; alternately, the breechblock itself can integrate a firing pin that will fire the next round upon its full closure.

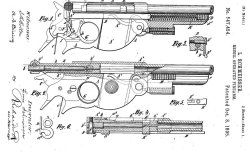

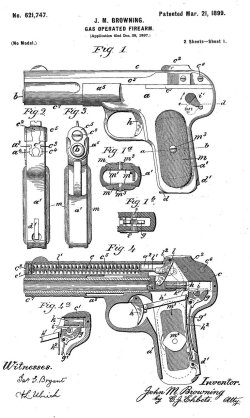

This is a very simple and effective system, generally known as “blowback”. Its earliest implementations can be traced as back as to the early semi-automatic pistols of the late 19th Century – chambered as they were with well-suited rounds for such a system, featuring relatively short cases and low-pressure propellant charges.

Those, just to name a few, were the early Bergmann pistols starting from the Model of 1894 (some of the earliest models didn't even have an ejector, and their rimless cases were extracted and ejected by the residual pressure in the chamber); Hiram Maxim's experimental pistol designs; and, finally, some of the most famous handgun designs of that time: the Browning model 1900 and 1903 handguns that set the stage for most semi-automatic pistols produced afterwards.

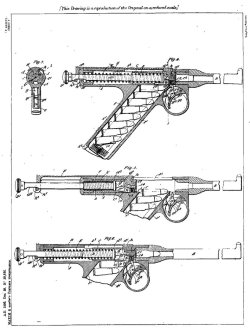

Later on, starting in 1918, this system was successfully applied to a new class of fully-automatic weapons: the sub-machine guns.

The first truly successful SMG design, the classic German-made Bergmann Mp18, featured a very simple cylindrical breechblock that cycled back and forth inside a tubular receiver. It was a highly successful setup, which was copied throughout the world, and still is used in a number of sub-machine guns in service with various military and Police forces.

Starting in World War II, a number of experimental and production-grade SMGs adopted a “wrap-around bolt” design, inspired by semi-automatic pistols, where a noticeable amount of the bolt mass would be concentrated in front of the bolt face, above or around the chamber, reducing the overall length of the gun while maintaining necessary mass of the breechblock.

During World War I and shortly afterwards, blowback operation was also successfully implemented in heavy automatic guns such as the 20mm Becker Type M2 cannon. Compared to other artillery pieces, these weapons were relatively low-powered, and used deep chambers and rebated rim cartridges to contain pressure for a slightly longer time during the initial stages of the reloading cycle. Today, similar blowback actions are successfully employed in a number of 30mm and 40mm automatic grenade launchers chambered to fire relatively low-powered charges that generate moderate pressures.

Despite its obvious advantages in terms of simplicity and low cost, the blowback operation also sports several noticeable drawbacks.

First and foremost, it is somewhat sensitive to the quality of cartridge case material and to the smoothness of the barrel chamber to ensure reliable operation and avoid case ruptures or torn rims.

Second, the mass of the breechblock has to balance the strength of the spring and the length of the breechblock cycle: if spring is too weak or the bolt is too light, the resulting force will be insufficient to keep the cartridge inside the chamber while pressure within the system is high. This could cause potentially disastrous conditions of ruptured or separated cases. If the spring is too strong, the gun will be hard to cycle manually; if the bolt is too heavy, its movement will cause excessive vibrations when fired, disrupting accuracy.

Also, as the cartridge power grows (in this case, the “power” is given by the internal pressure level multiplied by the inner area of the cartridge base), so grows the bolt weight level necessary to keep the cartridge in the chamber. Normally, sub-machine guns chambered to fire the 9x19mm Luger ammunition sport a breechblock weighting around a 0.5 kg.

With an intermediate cartridge – such as the Russian 7,62x39mm M43 – the necessary weight of the breechblock would rise to about 2 kilograms, and with earlier typical military rifle cartridges, e.g. 7,62x51mm NATO, the breechblock would have to weight something around four to five kilograms, making a blowback system absolutely impractical (not mentioning the inherent unreliability due to the very high pressure levels involved).

This ain't a great deal when dealing grenade launchers, since those systems generate noticeably lower pressures and are usually mounted on tripod or vehicles for stability; the increased dispersion, caused by a heavy breechblock oscillating back and forth inside the gun is also not an issue for weapons which are normally used against “area targets” rather than against “point targets”.

As mentioned above, the usefulness of the blowback operation principle is limited by the rearwards pressure level, generated by a cartridge being fired, which dictates the weight of the breechblock and the strength of the spring.

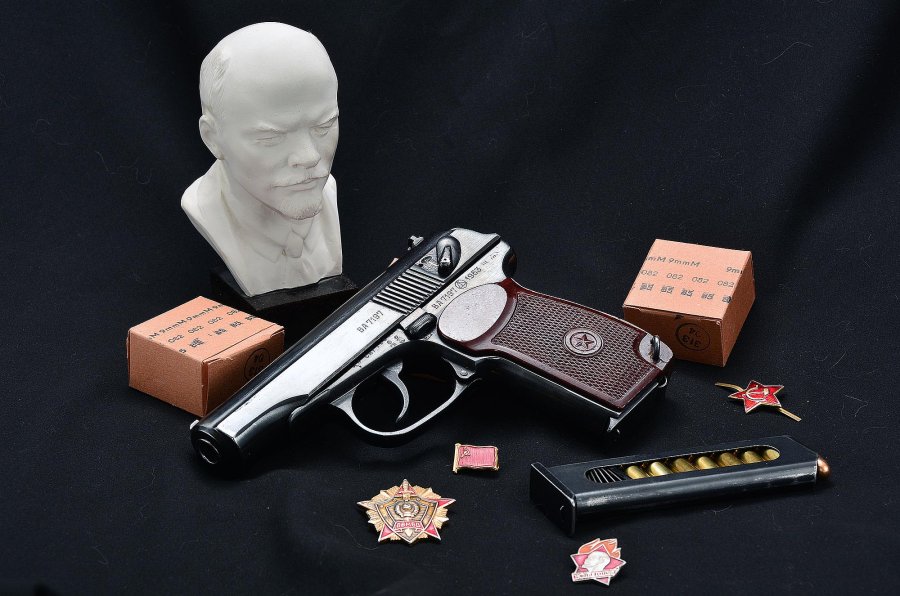

For handguns, which are normally limited in weight to 1 kg and even less, the 9mm Luger caliber represents the cut-off line for the use of a straight blowback system. While some practically working pistols were indeed built to fire the 9x19mm round using a blowback system – such as the Heckler & Koch VP70, or the currently-produced, US-made Hi-Point line – most blowback-operated handguns are chambered to fire relatively low-power rounds such as the 9x18mm Makarov round, the .380 ACP caliber, and others even smaller.

Shoulder-fired guns such as pistol-caliber carbines and sub-machine guns can accommodate heavier bolts, and are thus often chambered in most major pistol calibers such as 9x19mm, .40 Smith & Wesson and .45 ACP, while retaining a straight blowback operation. No blowback-operated rifle or machine-gun chambered to fire an intermediate or full-power cartridge was ever mass produced.