The key reason for the slow start was the propellant powder and its burning characteristics. Until advent of the smokeless powder, thick black powder residue tended to clog or jam even the most sturdy manually operated firearms such as revolvers after just a few dozens of shots. Early smokeless powders produced noticeably less residue, but their internal ballistic properties varied widely depending on the powder type and batch, environmental conditions etc.

Variations of the pressure at the gas port, drilled in the bore to bleed the gas to the operating piston, caused variations in the velocities and impulses of the moving parts, affecting reliability and durability of the guns. Also, due to insufficient knowledge of the processes that happen inside the bore during the discharge, many were afraid of gas port erosion, decrease of the muzzle energy (due to gas bleeding off from the bore) etc. As a result, gas operated systems became truly prolific only during the interwar period. By the end of WW2, gas operated action became the preferred system for most automatic long guns, thanks to advancements in metallurgy, propellant chemistry and internal ballistics science

Compared to recoil operated actions, most gas operated guns offered better accuracy due to stationary barrel, and somewhat lighter construction due to lack of necessity for a long barrel jacket. In fact, almost all WW2 era semi- and full-automatic hand-held long guns that fired rifle or intermediate ammunition were of gas operated design. All major self-loading and automatic rifles of the era (US M1 Garand and M1 Carbine, Russian Tokarev SVT-40, German G.41, G.43 and StG.44) were of gas operated design; in production numbers they outshadowed the only recoil-operated rifle, US Johnson M1941, by more than 100:1 magnitude. Today, gas operated actions dominate in most types of hand-held and mounted “long” small arms, gradually replacing few older recoil-operated (MG-3 or Browning M2HB) or delayed blowback (HK G3 and HK33) weapons still in service.

There are only two closely linked classes of automatic firearms where gas operated actions have very little influence – handguns and submachine guns. Both fire relatively low-pressure rounds from relatively short barrels; as of today, there’s only one production handgun (the famous and monstrous “Desert Eagle” by Magnum Research) and less than a half-dozen submachine guns that use any sort of gas operation. Most pistols use either blowback system or short recoil system; most submachine guns use simple blowback.

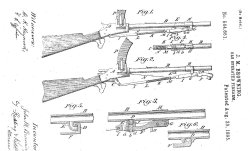

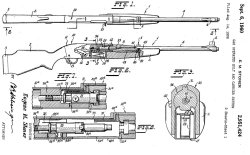

It is interesting to note that basic principles of gas operated, locked breech firearms were invented and patented before or shortly after the turn of the XX century. One of the earliest gas operated designs belongs to French brothers Clair, who patented a gas operated rifle as early as 1892. Their weapon featured gas cylinder, located below the barrel and connected to the bore via gas port.

Upon discharge, hot powder gases are fed to the cylinder through said port, pushing the piston forward and thus compressing a strong action spring. Once this spring is fully compressed, the gas pressure is released and the power of the compressed spring is used to cycle the opening action of the gun. This system, later repeated with similar lack of success in several designs, sought smooth operation of the action regardless of the variations in the pressure and violent nature of powder gases.

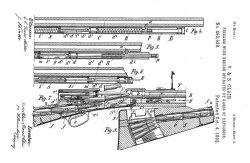

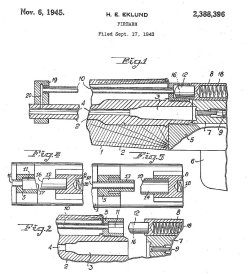

In 1895, John Browning patented his own version of the gas operated action. He also used a hole drilled in the barrel (his earliest experiments were conducted using muzzle blast), but his patent used an oscillating piston which resulted in gradual opening of the breech, thus helping to ensure slow initial extraction and avoid torn rims and split cases.

It is interesting that his patent also contained a simplified design with blow-forward piston, but it was not used by inventor for the reason described above. In fact, Browning’s gas operated machine gun, produced by Colt as their Model 1895, was one of the first successful military gas operated weapons. Known as a “potato digger” due to its piston swinging below the barrel and digging the dirt if its barrel is too close to the ground, this weapon served through several minor campaigns and one very large Great War.

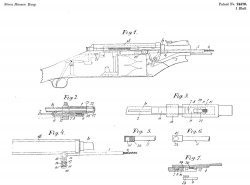

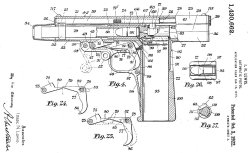

Apart from machine gun, Browning also patented a semi-automatic gas operated pistol with swinging piston located above the barrel; hardly a practical gun, it was never put into production unlike much more famous blowback and short-recoil operated handguns from the same designer. At about the same time someone Carl Ehbets, an employee of the Colt Firearms who worked closely with John Browning, also patented an interesting gas operated pistol. It used a gas cylinder below the barrel, connected to the bore of the gun, and a long stroke piston that moved rearwards under the pressure. Upon discharge, rearward movement of the piston first unlocked the bolt, and then cycled it back for reloading. Basically, it was as modern a system as it goes.

At this step we must divert a bit from our historical retrospective and discuss some basic types of the gas operation. As said above, the basic principle of this system is to use pressure of burning powder gases to operate certain moving part (usually known as a “piston”), which in turn would transfer its movement to the action parts to unlock and open the breech, ejecting a fired case in the process; feeding a fresh round, closing the breech and locking is usually conducted by a spring, compressed during the first part of the cycle.

Gas operated systems can be classified by following attributes:

1. Location of the gas cylinder and piston. Most popular variations are:

A. below, above or to the side of the barrel, with gas cylinder running in parallel with the bore and connected to it through a gas port (a hole drilled in the side of the barrel)

B. around the barrel, somewhere along its length or at the muzzle. In the first case, gas cylinder is formed by the external surface of the barrel and enclosing tubular cylinder, and the gas piston has annular shape; gas cylinder is connected to the bore via one or several gas ports. In the second case, there are two further variations. Either the gas cylinder is similar to the previous design but extends forward of the muzzle, capturing muzzle blast to push the annular piston rearwards, or the gas piston is a cup-shaped affair with small hole in its base for passage of the bullet. In this case, muzzle blast pushes the cup-shaped gas piston forward.

C. There’s no separate or “dedicated” gas cylinder per se; hot powder gases are fed from the gas port in the bore and through the gas tube towards a bolt carrier, where they either impinge on the bolt carrier itself or are fed into internals of the bolt group to expand there and force the bolt carrier rearwards against temporarily stationary bolt.

2. Length of the piston stroke. Generally speaking, there are two systems, known as “short stroke” and “long stroke”. With long stroke systems, gas piston is rigidly attached to the breech block / bolt carrier and moves rearwards for entire length of the action cycle (even if the actual length of the “active” part of the cycle when gas makes its job is noticeably shorter). In short stroke systems gas piston is invariably a separate part of group of parts that give a bolt group a short “tap” before stopping in its track and leaving the bolt group to complete its reloading cycle alone.

One of less obvious benefits of the gas system that uses a gas port is that it can be easily adjusted for various environmental and other conditions. Changing the cross-section of the gas port directly affects amount of hot powder gases allowed to act on the gas piston, thus varying the power available to cycle the gun. This can be used to ensure reliable functioning under various conditions (i.e. to add power to the system if the gun is too clogged after prolonged use), or to vary rate of fire (which is especially useful for machine guns). There are many variations of gas regulator systems that can offer anything between two and more than twenty settings, with some also offering a complete gas cut-off (useful for use with sound suppressors or with certain types of muzzle-launched rifle grenades).

Some weapons feature various automated gas regulators that ensure reliable functioning with wide variety of loads. This feature is quite useful in hunting shotguns which can be used with broad variety of loads, from light “sporting” loads to heavy magnum loads with slugs or shot. The simplest automatic gas regulator usually is made as a spring-loaded valve, which bleeds off to the atmosphere excessive powder gases. The higher is pressure inside the gas cylinder, the more gas is allowed to escape before affecting the gas piston.

It must be noted that despite wide variety of gas systems designed during the last century and the quarter only few remain truly popular over the years. In regard to the placement of the gas piston, it is usually located above or below the barrel, most usually opposite to the feed system. I.e. on most gas operated belt fed machine guns belt feed unit is above the barrel and the gas cylinder is below; on most modern rifles gas cylinder is at the top and magazine is at the bottom.

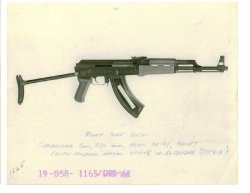

There are obvious exceptions for this rule, such as some early self-loading and automatic rifles (French M1917, US M1 Garand and M14), as well as most gas operated shotguns (where annual gas piston is located around the magazine tube that runs below the barrel). Use of long or short stroke piston is also arbitrary; it is generally accepted that short stroke pistons are more conductive for accuracy (good examples are Dragunov SVD or HK 417 / G28 sniper rifles), while long stroke pistons are more conductive for reliability under harsh conditions (best examples are Bren machine gun, M1 Garand and Kalashnikov AK).

Annual gas pistons are rarely used in anything except the shotguns, which normally operate under lesser pressures compared to rifles. Muzzle cup actions are the thing of the past, because they require very long action rods and badly affect balance of the rifles. The last, but not least is so called “direct impingement” action that features no visible gas piston at all.

Originally devised by French designers during late 1920s, this type of action fed the powder gases through the long gas tube directly to the forward face of the bolt carrier, which itself served as a piston. After the WW2 this system was taken further by Eugene Stoner, who allowed the powder gases to enter the hollow bolt carrier body and expand inside, against the bolt head at the front and the inner bolt carrier wall at the rear. This system is especially conductive for accurate shooting, because of symmetrical forces applied to the bolt group, but it is also more sensitive for fouling and “dirty” powders than piston-operated actions.

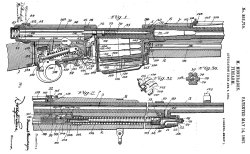

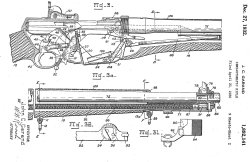

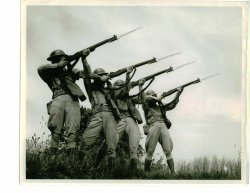

Long stroke gas operated systems are oldest and probably most widespread in the world. Starting with early guns such as Hotchkiss M1899 machine gun, Lewis machine gun of 1912, French RSC M1917 semi-automatic rifle and Browning BAR M1918, this system was later used in many highly successful designs such as Czechoslovak ZB-26 light machine gun, US M1 Garand rifle and Kalashnikov AK assault rifle, along with its many descendants. Long gas piston adds noticeable weight to bolt group, slowing down its rearward movement due to initial inertia and then maintaining high reliability due to same inertia once parts acquire some speed.

Short stroke systems appeared “en masse” during inter-war period in several semi-automatic rifles. One benefit this system offers for rifles is that bolt carrier is not coupled to the action rod, connected to the piston. That way, conveniently located top piston does not interfere with top loading of the rifle using stripper clips, a feature preferred by many military “customers” up until late fifties. To name few most popular rifles that used short stroke action that way, there were Russian Tokarev SVT-40 and Simonov SKS-45, German Kar.43, Belgian FN-49 and FN FAL.

American M1 carbine and M14 rifle stood a little separately there, as they have gas piston located below the barrel, which results in an intricately bent action bar, similar in concept to that used in M1 Garand rifle. Most modern rifles that use short action pistons dispensed with clip loading and use top gas pistons with simple action rods that impinge on the front of the bolt carrier. Most prominent weapons of this type are US AR-18 rifle and many of its spiritual descendants, such as German HK G36 or British L85A1.