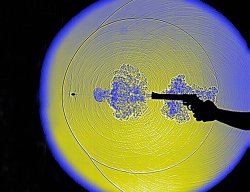

Let’s start to analyze what is hearing and what can damage it. Sound is nothing more than pressure waves in the air.

A vibrating object (say the string of a guitar) moves the molecules of air surrounding it in compression-depression waves with a specific frequency (that is, the distance between two pressure wave fronts).

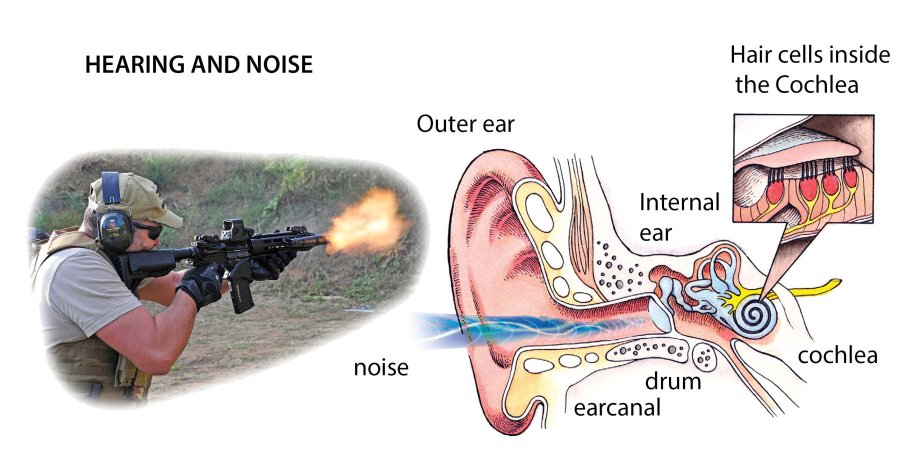

The human ear detects sound by means of a thin membrane, the tympanum, that through a leverage system composed of three tiny bones transmits the pressure waves to the cochlea: this is a spiralling structure like the shell of a snail where a myriad microscopic hairs, called stereocilia, are connected to nerve terminations. In the same way that different length guitar strings (produced by pressing your fingertips on the frets) produce different frequencies, different length stereocilia oscillate responding to different frequencies of sound.

If a sound (pressure wave) is too strong, the impulse given to the specific stereocilia group can bend some permanently, so that they won’t respond to this frequency anymore. If enough are permanently bent, we will lose that frequency from our hearing capabilities. This is the first and main mechanism of hearing loss: it can happen through a single, very violent exposure or multiple strong exposure or continuous excessive exposures. In this case, hearing loss is also frequency-dependant. We will loose hearing in the frequencies where the hairs are most stressed.

The second hearing loss cause is any kind of lesion to the tympanum: a strong pressure wave can cause a laceration in the thin membrane. Unless the membrane is completely broken, such laceration will heal, but scar tissue will change the flexibility of the membrane, which will become less sensitive and will change the way it transmits certain frequencies. To cause this kind of damage you need a lot of noise.

The third, most grievous kind of hearing loss is caused by such a pressure wave that it not only disrupts the tympanum, but also fractures the tiny bones in the inner ear.

This kind of damage produces total hearing loss and can be sometimes corrected with ear surgery, but most often than not is permanent.

Luckily enough, an enormous amount of sound (bomb blast level) is needed to cause such destrucion.

You need a far higher level of impulse noise to damage the stereocilia than what is needed with continuous exposure, so our ears are quite more resistant to impulse sounds (like a gunshot) than they are to a continuous noise (like machinery or music in a disco).

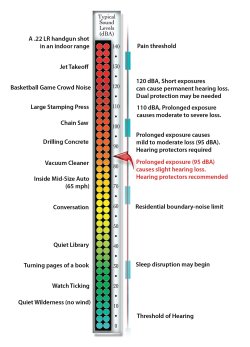

Sound volume is measured in decibels (dB), on a logarithmic scale, meaning that 10 more dB means a tenfold increase in power. So a 20 dB sound is 10 times as powerful as a 10 dB sound, a 30 dB sound is 100 times as powerful, a 40 dB sound is 1000 as powerful and so on.

To give some perspective to this scale, a sound level of 55 dB is that of a normal conversation, 70 dB is a vacuum cleaner, 80 dB is a heavy trafficked road, 85 dB is the limit of hearing damage for continuous exposure, 90 dB a lawnmower, 100 dB is a jackhammer, 120 dB is the limit for hearing damage from short duration noises and 130 dB is the so called “pain threshold”: sound is actually painful.

A typical 9mm Luger shot will stop the sound meter at 159 dB: far beyond the limit of hearing damage. But it’s also a very short lasting sound, and the human ear has defensive capabilities that can briefly shield it from strong noises, so a single shot, or even a half dozen, won’t produce serious damage to your hearing. Repeated shooting without proper hearing protection will.

Hearing protection comes in two types: earmuffs and plugs. Earmuffs cover the outer ear, while plugs are inserted into the ear canal.

Contrary to popular belief, if you are using plugs sound doesn’t travel “through bone in your skull into the inner ear”, so the choice between plugs and earmuffs is just a matter of personal choice and comfort. Some feel the earmuffs are too hot in summer and are uncomfortable while shooting rifles, other find the feeling of the plug in the ear canal annoying.

There’s also no difference in sound reduction levels. Basic (compact) earmuffs and foam plugs typically offer a sound reduction around 20-25 dB, while full size muffs and well fitting silincone plugs may offer a protection of up to 35 dB.

This levels are “average”: each protective device will offer different levels of attenuation for different frequencies. It’s important that the best attenuation levels are within the typical frequency band of a gunshot.

This effect is exploited in a useful way by some kind of plugs that offer high attenuation against the frequencies of a gunshot, but low attenuation in frequencies typical of speech, allowing the wearer to understand other people while being protected from the noise of most small caliber cartridges.

Now, I see an objection coming: you just said that anything over 120 dB is bad, but if the best protection only dampens 35 dB, this still leaves 124 dB of sound level when we fire our 9mm. This is true, but most of the blast of the gun is directed forward, so the shooter is experiencing a much lower level of noise. Incidentally, the best sound moderators available (often misnomed “silencers”) will have an attenuation of about 35 dB, much like a good pair of ear plugs. Still a lot of noise, well beyond the Hollywood “PFUT” sound.

So, wether we are shooting at the range, or hunting, or training, we should always wear the best hearing protection we can afford.

A good pair of reusable plugs or earmuffs come at about 15-20 bucks and they are worth their weight in gold. Don’t let peer pressure or “macho” attitude deter you from using hearing protection. Having to ask your intrlocutor to repeat every other sentence is far from cool.

When I was in the army, I bought a pair of shooting earmuffs the day before we went to our first live fire training session. The other guys in my squad laughed. By the end of the 7,62 fire session (BM-59 with its characteristic – and very noisy - compensator) they all asked me where I had bought them. The next time, we all had them.

Unfortunately, I suffered partial hearing loss from years of motorcycle riding without hearing protection, because I wasn’t smart enough to figure out by myself that wind roaring loud enough to overwhelm the sound of a Harley engine wasn’t good for my ears, but that’s another story.

I talk about it only to emphasize that you should wear hearing protection whenever you are exposed to strong sounds of any kind. Hearing damage is irreversible, and tinnitus (buzzing in your ears) is a very annoying and unfortunately faithful companion that, once acquainted with, won’t leave you for the rest of your life. Prevention is the only way.