There are actually no such things as "bad" knives, if you know their original intended use. It should be obvious that you can hardly shave with a bowie knife. And on the other hand, a razor that is actually ultra-sharp can't be used to cut branches or tomatoes and cucumbers (for those who want to know more: the acid of the tomatoes would attack the non-stainless carbon steel of the razor, and the hard branches would even break tiny pieces out of the cutting edge). Knives are therefore subject to different requirements. That is why it is important to choose the right steel according to the intended use. The composition as well as the percentage distribution of the alloying constituents differ in part considerably for each steel grade and give it quite individual properties. However, we will not go into the depths of metallurgical knowledge here (there are excellent reference books for this, but they are often difficult for the layman to understand), but want to provide you with a practical guide. The hardness of the steel is an important factor: to be suitable as a blade material, the steel must have a hardness of at least about 55 HRC (Rockwell hardness). Non-shock load tested blades have a hardness of 60 to 65 HRC. For one-hand knives such as kitchen or hunting knives, an HRC value of 57 to 60 is recommended due to the lower brittleness of the material.

Nowadays, most knife manufacturers specify the types of steel used for their products. Either the respective designation is written on the blade or the buyer can read the desired information in the catalog or on the website of the manufacturer or dealer. Provided, of course, that it is a branded knife. With imported cheap goods from the Far East, this can of course also be the case, but here you will usually only find a general reference such as "stainless". It is then often a rust-resistant "single steel" of low hardness and inferior quality (but this does not mean that all cheap knives have no utility value. It always depends on the demands of the owner and his purchasing budget). Let's start from high quality knives, which should be efficient for a longer period of time. Since each steel has its own special advantages, it depends on the choice of the right type.

Thus, a hunting knife should have a good sharpness and keep it as long as possible. It is purely a cutting tool. So wear resistance is required here, and the blade hardness must be correspondingly high. The right choice here would be a steel with a high carbon content. This determines the achievable blade hardness. A camping knife, on the other hand, is designed more for rough use and must also withstand impact work, such as chopping branches. A high hardness here, however, would increase brittleness and lead to chipping on the blade, and one could hardly "leverage" with the blade. The preferred property is therefore toughness, which goes hand in hand with lower hardness. The carbon content should be lower here or the achievable hardness of the blade should not be fully exhausted in the manufacturing process.

What and how much of it should be in the knife steel?

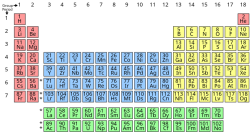

Carbon is the most important element. It is only through the addition of carbon that iron becomes steel and makes it hardenable. Other important "ingredients" for stainless steels include chromium, molybdenum and vanadium. These are chemical elements (link to Wikipedia) that are added ("alloyed") to the steel to improve material properties in the desired way.

- Carbon (C): among other things, its hardenability depends on it and is what turns iron into steel in the first place.

- Chromium (Cr): provides rust resistance at a minimum content of thirteen percent.

- Molybdenum (Mo): increases cutting and fatigue resistance and counteracts susceptibility to corrosion.

- Vanadium (V): increases cutting ability and also improves toughness and fracture strength.

- Manganese (Mn): binds excess oxygen and degasses the melt. At the same time, hardness and toughness are increased if the alloy content is not too high.

- Silicon (Si): degasses the melt. At low levels, tensile and compressive strength improve.

- Phosphorus (P): is ...undesirable. It increases the hardness, but makes the steel brittle at higher alloy content.

So if you want to know something about the potential of your knife blade, always pay attention to the steel grade used. In Europe, this is classified according to DIN (German Institute for Standardization). Alternatively, the chemical composition corresponding to the respective steel grade is also indicated. In contrast, most steels produced in the USA or Asia are classified according to AISI (American Iron and Steel Institute), the American Iron and Steel Industry association.

Despite different designations of material numbers according to DIN and AISI, steels can also be largely identical due to the same compositions. However, differences in quality can't be ruled out.

Materials for knives: standard steels according to DIN compared to AISI

- DIN WN 1.4034 (X46Cr13) = AISI 420 (hardness up to approx. 54 HRC)

- DIN WN 1.4110 (X55CrMo14) = AISI 440 A (hardness up to approx. 56 HRC)

- DIN WN 1.4112 (X90CrMoV18) = AISI 440 B (hardness up to approx. 57 HRC)

- DIN WN 1.4125 (X105CrMo17) = AISI 440 C (hardness up to approx. 60 HRC)

The individual steel components and their percentage make up the quality of the respective steel grade and thus largely determine the possible applications of the blades made from them.

A DIN knife steel often used in the blade industry has the material number (WN) 1.4116. Its designation is X50CrMoV15, which indicates the composition of the steel: 0.50% carbon, 15% chromium and smaller amounts of molybdenum and vanadium. The carbon content makes it possible for this steel to have a maximum hardness of about 56 to 59 HRC. The sufficient chromium content ensures corrosion resistance, the molybdenum provides strength or toughness, and the vanadium additionally counteracts the risk of fracture susceptibility. These are properties that are ideally suited for a universal knife blade, as they represent a very good compromise in terms of rust resistance, edge retention and toughness. An example: the Puma chef's knife priced at 79 euros (RRP), pictured with yew handle scales.

The steel selection options are extremely extensive due to rapid further developments and state-of-the-art manufacturing processes. This applies equally to domestic and foreign grades used in knife making, which have very specific properties. Some knife manufacturers also give the steels they use their own names, the recipe of which is not disclosed for marketing reasons and which, unfortunately, do not make the purchase decision any easier as a result.

Typical knife steels and their properties

DIN 1.4034 / AISI 420: this stainless steel contains relatively little carbon and mainly chromium (approx. 13%). The achievable hardness is around 54 HRC. Due to its low hardness, this grade is not very susceptible to breakage. However, a blade made of it must be resharpened more often. In earlier decades, 1.4034 was often used in blade manufacturing and had a very good reputation due to its careful, standard-compliant production and proper heat treatment. Nowadays, there are many low-budget knives from the Far East on the market that have blades made of AISI 420. Despite the same components, however, there can unfortunately be quite considerable differences in quality which, by equating them, often wrongly make DIN 1.4034 look like cheap "simple steel".

DIN 1.4110, 1.4112, 1.4125 / AISI 440A, 440B, 440C: this group of stainless steels has a decades-long tradition of use for blades. Because they have other alloying components, such as molybdenum, in addition to chromium, they have become widely established in the knife world. The main differences are, in ascending order of numbers, a higher carbon content and the associated better edge retention. The most familiar to the price-conscious customer should certainly be the 440C steel, which is considered a good starting steel for knives that are easy to resharpen and have a long edge retention.

Powder Metallurgy Steel (PM Steel): most knife steels are melted with the selected elements and then processed according to their intended purpose. However, since the "ingredients" cannot always be introduced in the desired proportion, another very innovative manufacturing method was invented a few decades ago.

In this process, the steel is atomized into fine powder, which is then "baked" together using heat just below the melting point and pressed under high pressure. In this way, more alloying constituents can be introduced into the steel than would be possible by conventional means, as they can no longer react with each other. This results in steels with very special properties that make a blade made from this elaborately produced material something special.

Damasteel: this is a powder metallurgy made steel from Sweden which can be given different damask patterns by using two different hardenable grades. It is produced in a similar way to the other PM steels.

In this Damascus stainless variant, the two steels are layered in powdered form and then compacted. After further processing, patterns are created which become visible after etching.

Traditional Damascus steel (not stainless): Damascus steel is still popularly said to have fabulous properties, but in the past it was created more out of necessity. In the early days of steel production, the precise control of important properties such as hardness and toughness was not yet possible. The result could only be seen after the blade was finished. In order not to obtain blades that were too hard or too soft, two pieces of steel with different carbon content were welded together and forged into a block by repeated folding and re-welding. This greatly increased the likelihood of achieving a good mix of wear resistance and flexibility for the resulting blade. The pattern did not matter at the time and only later gained importance as a visual sign of the smith's skill. The blades made in this way were, of course, not yet stainless.

Traditional Damascus steel (stainless): nowadays, stainless Damascus steel is also available. Since chromium-alloyed steels cannot be welded due to the oxygen present in the air, this process is carried out in an inert gas atmosphere. This manufacturing process was invented only a few decades ago. It does not detract from the old tradition of Damascus forging, but adds an innovative component.

Laminate rolled Damascus: this Damascus variant has a core layer of stainless steel, to which several layers of also corrosion-resistant steel are rolled on both sides. This multi-laminated blade is thus given a Damascus pattern.

The number of layers is always odd (usually 67, 69 or 71). The advantage of such a blade is not an optimization of the steel properties, but primarily the visual effect.

The production can of course be done with a high automated effort and therefore cheaper than with manual work.

Sandvik 12C27 / 14C28N: both steels are stainless and are also colloquially referred to as "Swedish steel". They differ slightly in their carbon and chromium content.

Despite good wear resistance, both grades can be resharpened well and are often used in the production of pocket knife blades and hunting and outdoor knives.

Classic carbon steel

Carbon steel: those who deliberately choose a non-stainless knife, choose this steel, which has only been added carbon and with which you can achieve a very fine cutting edge. Despite high edge retention, such blades are easy to resharpen and also allow for coarser use.

Although stainless steel was invented over a hundred years ago, carbon steel knives still have their raison d'être and are popular for many applications. Many kitchen knives from the well-known Solingen companies have carbon steel blades and are popular for their durability. But also the various razors have mostly carbon steel blades, can be easily resharpened daily on the leather strap, but are sensitive to moisture and must be carefully dried after shaving.

DIN 1.2379 / AISI D2: whether this tool steel is actually corrosion resistant or not is often answered differently. The chromium content is around 12%. This is only slightly below the 13% limit required for a stainless steel. However, the carbon content of 1.5% is very high. Since a high value of carbon must also be countered by analogy with a higher proportion of chromium, it is not possible to speak of "stainless" in this case. In addition, the chromium in D2 is not evenly distributed in the steel structure, but is literally bound like "lumps in a soup". In short, this steel is at best somewhat more rust-resistant than pure carbon steel.

Many thanks to Puma Knife Company from Solingen for the technical information and photos! Puma manufactures hunting, sport and leisure knives. In a city whose name is not without reason a protected trademark for quality knives and scissors: Solingen. Puma lives up to the high standards of this city and has been impressing with the highest quality in material and workmanship for over 250 years.